On a May 2009 afternoon in Philadelphia, seven weeks after he turned 21, Clayton Kershaw walked into the visiting manager’s office at Citizens Bank Park. One night earlier, the Phillies had pilloried him, scoring four runs in five innings, benefiting from Kershaw’s recurring inability to throw strikes. Kershaw understood what an invitation to sit with the skipper usually meant. He suspected he was being demoted — maybe from the starting rotation, maybe from the team itself. Joe Torre had another idea in mind. He decided to stage an intervention.

Seven starts into his second season, Kershaw was teetering on the brink of a return to the other side of the bridge. The offseason departures of veteran pitchers Derek Lowe and Brad Penny created an opening for Kershaw. He had responded with a 5.21 ERA midway through May. He displayed the same maddening qualities from his rookie year. His fastball sizzled and his curveball popped eyes, but he failed to command either. His changeup remained toothless. Ned Colletti suggested a return to the minors. Torre asked to extend Kershaw a little more rope. Kershaw reminded Torre of his former middle infielders in the Bronx. Like Derek Jeter, like Robinson Canó, Torre appreciated how Kershaw handled misfortune. He deserved a chance to grow in the majors.

Inside Torre’s office, Kershaw sat with his manager, pitching coach Rick Honeycutt, and hitting coach Don Mattingly. Kershaw had appeared in 28 big-league games. The three coaches had combined to play in 53 big-league seasons. Torre figured their collective wisdom might break through. He lobbed Mattingly a question.

“If Clayton was pitching today,” Torre began, “how would you face him?”

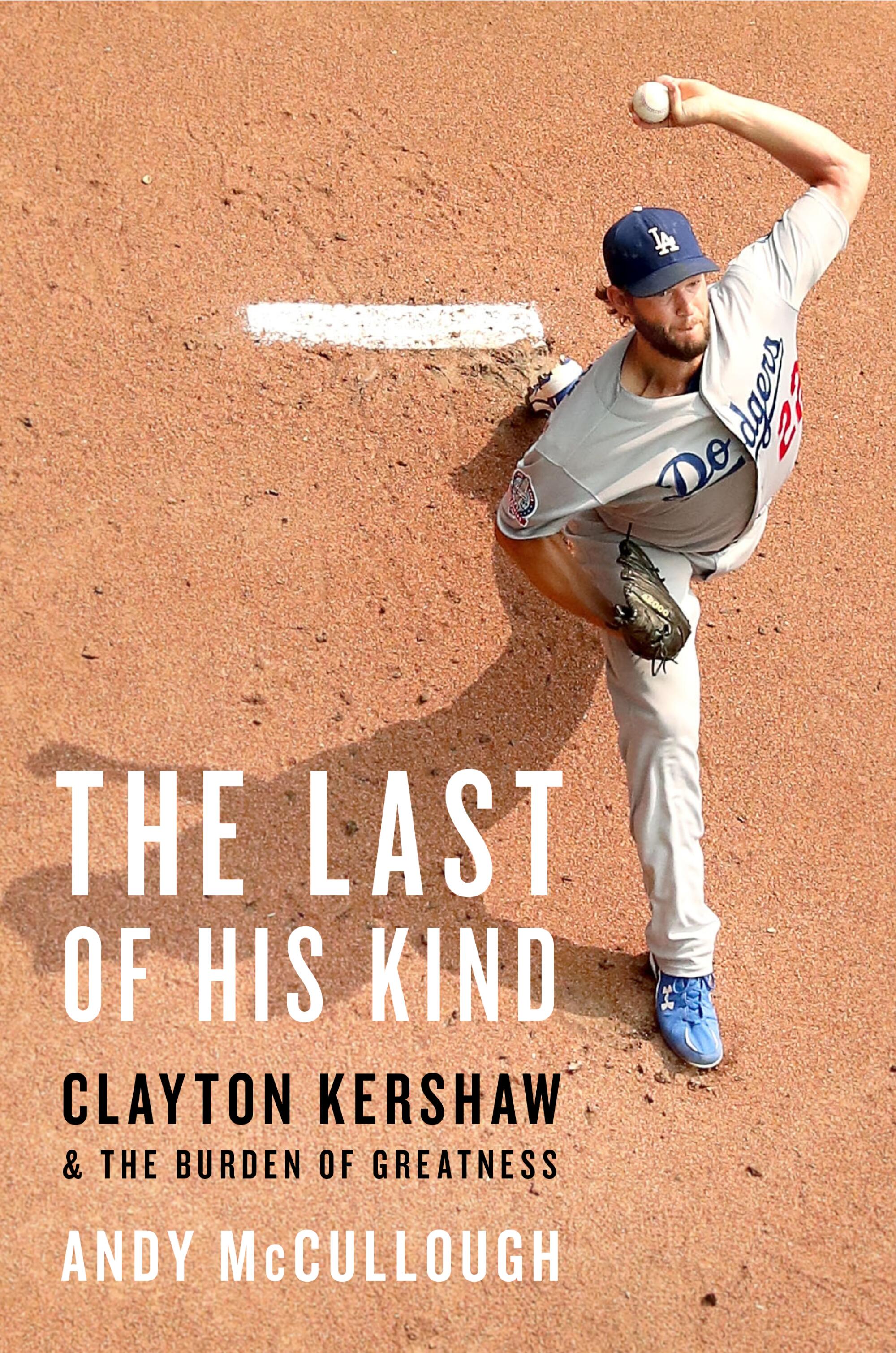

The cover of “The Last of His Kind.”

(Hachette Books)

Mattingly had been one of the finest hitters of his era, Donnie Baseball in the Bronx, a six-time All-Star and nine-time Gold Glover at first base. He unspooled a devastating scouting report. He would cut the plate in half, because he knew Kershaw only threw inside, Mattingly explained. He would ignore the curveball, because he knew Kershaw could not command it. He would disregard the changeup, because he knew Kershaw did not trust it. He would focus on the inner half and wait for heaters. “He has one pitch,” Mattingly explained. “Hit the fastball. It’s not that hard.”

Torre opened the floor to Kershaw.

“Do you know what you need to do?” Torre said.

“I know,” Kershaw said. He had been hearing about this for weeks. Months. His whole brief big-league career, really. “I need to throw my curveball for strikes.”

Torre was patient but firm. The coaches appreciated the kid’s obstinance. All the great ones, they thought, exhibited some level of defiance, some refusal to deviate from their internal compass. “That’s how they got to be good,” Honeycutt explained. “They are stubborn in their belief, and their belief in themselves.” Kershaw had a chance to be one of those. But he wasn’t yet. To flourish, Torre explained, he required adaptation.

“You need to figure out a third pitch,” Torre said.

He had heard this mantra ever since the Dodgers drafted him. The changeup galled him. He could not make the pitch meet his standard.

It was not for lack of effort, he believed. When he threw his fastball and his curveball, his left wrist flicked naturally across his body. To throw the changeup, he needed his wrist to snap in the other direction, a process called pronation. “I can’t pronate,” Kershaw explained. “I don’t know how to do it.” Yet he kept trying, all through the spring of 2009, at the behest of the organization. Lefties were supposed to throw changeups and Kershaw aspired to be the best left-handed pitcher he could be.

For the Dodgers, 2009 was a year of transition. The team no longer trained at Dodgertown. Frank McCourt had found a new home outside the city of Glendale, Arizona, called Camelback Ranch. The Dodgers shared the complex with the Chicago White Sox. Grimy barracks and muggy Florida weather were replaced by clear skies and new facilities. The decisions made by McCourt and his wife, Jamie, would have dire consequences for the Dodgers in the coming years, but in the spring of 2009, there was still tranquility. In that first year in the desert, Honeycutt hooked Kershaw up with Koufax. “How can you not?” Honeycutt recalled. Honeycutt was curious if Kershaw could replicate some aspects of Koufax’s delivery, the famed catapult that delivered his fastball and curveball, “the kinetic equivalent of E. B. White’s ‘clear, crystal stream’ of the English language: honed, pared down, essential,” Jane Leavy wrote in her biography of Koufax. The man told Kershaw the keys of his movement, like anchoring his left leg to the rubber, his right hip propelling him toward the plate.

Dodgers manager Joe Torre pats starting pitcher Clayton Kershaw on the back as he removes him from a 2009 game against the San Diego Padres as catcher Russell Martin (55) stands beside them.

(Stephen Dunn / Getty Images)

The actions did not come naturally to Kershaw. He radiated dissatisfaction with the process, his frustration apparent to Randy Wolf, a kindly 10-year veteran lefty signed to fill out the rotation. One day in the weight room, Wolf encouraged Kershaw to trust his instincts. “One thing I’ve learned,” Wolf told him, “is you don’t really learn from freaks.” No one could be like Koufax, Wolf explained. But Wolf had been around long enough, and seen enough of Kershaw, to recognize something else. In 15 years, Wolf continued, there would be kids lifting their hands and feet in a fluid motion and pausing before exploding toward the plate. They would try to imitate Kershaw. And they would fail. “Because you’re a freak,” Wolf said.

Kershaw turned 21 that spring and bought his first beer; he sipped it for a while but declined to order a second. He showed his age in other ways. Over the winter, he bought a townhouse near Highland Park. He purchased a Ping-Pong table as his first piece of furniture. A dry-erase board for scorekeeping hung nearby. Searching for a haircut that summer, he fretted he could not find a Supercuts. The nearest salon tried to charge him $42. “How much for a buzz cut?” Kershaw countered. He haggled for a $24 shaved head.

His youthful obstinance was less amusing when it came to the game. Because he never cut corners, because he trusted the five-day cycle, he thought he knew best. After one shoddy outing at Dodger Stadium, Kershaw walked to the parking lot with Mike Borzello. Kershaw asked Borzello for a diagnosis. “You can’t throw a curveball for a strike,” Borzello said. When he missed with the curveball, he always came back with a fastball. The heater was special enough that even big-league hitters couldn’t always handle it. But they could foul it off, drive up his pitch count, and wait for a mistake. Borzello suggested Kershaw throw a different type of curveball, one that sacrificed some of that beautiful movement, the spin that made Scully swoon, in exchange for one that could reliably land in the strike zone. Kershaw did not like that idea.

“I’ve always thrown my curveball one way,” Kershaw said. “I’ve always thrown it as hard as I can.”

Borzello chuckled. “Against who? High school kids? A-ball?” Borzello said. At this level, Borzello explained, starters needed off-speed pitches they could control. Borzello warned him of the consequences. “If you can’t do that here, then you’re not going to survive,” he said. “You’re going to be a reliever.”

After meeting with Torre, Honeycutt, and Mattingly after several weeks of getting pounded, Kershaw understood the stakes. He refused to mess with his curveball. The changeup eluded him. That left one other option. He asked Honeycutt about a slider.

Rick Honeycutt grew up outside Chattanooga, Tennessee, and wore the orange and white for the University of Tennessee Volunteers in Knoxville. He spoke as if each syllable had been dredged through the Chickamauga Dam. He debuted in the big leagues at 23. He retired at 42. In the intervening years, he made an All-Star team in Seattle, collected an ERA title in Texas, and won a World Series in Oakland. He had been a top-tier starter and he had been a second-rate reliever and he had been everything in between.

To Honeycutt, his most transformative experience came after the Rangers traded him to the Dodgers. His first spring at Dodgertown in 1984 blew his mind. He lapped up conversations with pitching coach Ron Perranoski, minor-league manager Dave Wallace, and an occasional spring instructor named Sandy Koufax. “I felt like I learned more in two to three weeks in spring training, just being around Sandy and Dave and Perry, than I had in my whole life,” Honeycutt recalled. In 2001, Wallace called him about rejoining the organization as a minor-league coach. Honeycutt felt the Dodgers had “gotten away from who we were” during the late 1990s, after the O’Malley family sold the team to Rupert Murdoch’s Fox Entertainment Group. Honeycutt joined the big-league staff as Grady Little’s pitching coach in 2006. Torre kept him around because Honeycutt connected with players and understood the organization’s history. “When I got hired, I wanted to bring back the influence of the past,” Honeycutt recalled. He favored humility over histrionics. He rarely yelled. He excelled at convincing even the obstinate to trust him.

Honeycutt had learned his slider grip from former Yankees pitcher Mel Stottlemyre. The slider was a simple pitch, less picturesque than a curveball but easier to command, breaking down and away toward the pitcher’s glove side. The grip was similar to that of a four-seam fastball, with the index and middle fingers overlaid on the ball’s red seam and the ring finger anchoring a few inches away. To make the ball move, the pitcher rotated his fingers, ever so slightly. Koufax taught Honeycutt how using pressure points tightened the spin. Koufax created a vise between his middle finger and the knuckle on his ring finger. He called it “hooking the seam.”

In the spring of 2009, as Kershaw searched for a third pitch to stabilize his career, Honeycutt offered to pass down what he had learned. “Clayton was a little stubborn about it,” Torre recalled. “But Clayton just loved Rick Honeycutt.” Kershaw did not need something that dropped jaws like his curve. He just needed something he could throw for strikes. Honeycutt displayed his slider grip and preached the principles he learned from Koufax, especially the pressure point. He told Kershaw to hook his middle finger deep into the seam. “I want you to feel like you’re pulling down, not across the ball,” Honeycutt stressed. Kershaw held the baseball in his left hand and mimicked the grip. Unlike the changeup, the slider did not force Kershaw to pronate. His wrist flicked just like it did with his other two pitches.

All the slider required, he discovered, was power. He threw the pitch as hard as he could and the grip took care of the rest. Kershaw tried it in between his starts and liked the shape. But he wasn’t sure it was ready. There were so many people in his ear — Honeycutt, Torre, Borzello, even Wolf. “The slider’s going to be so much easier to command,” Wolf told Kershaw. Explained A. J. Ellis, “He’s a late listener. He hears what you say. Because he’s a stubborn person — probably another attribute that makes him great, but also makes him a joy to work with. But he’ll come around to things.”

Dodgers pitcher Clayton Kershaw throws from the mound against the Florida Marlins at Dolphin Stadium on May 17, 2009. At the time, the Dodgers were urging Kershaw to add a new pitch to his arsenal.

(Ronald C. Modra / Getty Images)

Kershaw delayed the implementation of the pitch for a few weeks. On May 17, in his first start after the meeting in Torre’s office, he carried a no-hitter into the eighth inning against the Florida Marlins. The bid looked serious enough that Honeycutt ducked into the Land Shark Stadium clubhouse and called Colletti for instructions. At a certain pitch count, Colletti insisted, Honeycutt had to intervene. The game prevented any controversy. Kershaw yielded a leadoff double in the eighth and exited immediately. Honeycutt and Torre exhaled — and then gushed afterward. “He’s got the Koufax dominance,” Torre said.

Except five days later, Kershaw took a step back. He walked four in five innings against the Los Angeles Angels. In Colorado, the Rockies scored three runs in six innings. “You could tell there was a discontent within him,” Wolf recalled. “No matter how he pitched, you could tell he was like, ‘OK. I can do better than that.’” After the game at Coors Field, the Dodgers flew to Chicago. Borzello was catching Chad Billinglsey in the bullpen located down Wrigley Field’s first-base line when Kershaw walked over. After Billinglsey finished, Kershaw asked Borzello to stick around.

“I’ve got a slider,” Kershaw said. “I want you to see it.”

Mike Borzello was Zelig in a chest protector. In the summer of 1997, Borzello was playing catch with Yankees reliever Mariano Rivera when the pitcher’s fastball darted without warning. The mysterious movement fostered Rivera’s Hall of Fame cutter. Nearly 20 years later, Borzello was coaching for the Chicago Cubs when the franchise ended its 108-year World Series drought. In between those milestones, Torre brought Borzello with him to Los Angeles.

Torre grew up in Brooklyn with Borzello’s father, Matt. Later in life, Torre and Matt Borzello ran a Southern California summer baseball camp for 15 years. Mike went undrafted out of California Lutheran University but signed with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1991, where Torre was the manager. Several years later, when Torre was managing the Yankees, he invited Borzello to become a bullpen catcher. Borzello was driving a truck for his father at the time. Torre opened doors, but Borzello kept them open. He possessed an intuitive understanding of swings and became an early adopter of video analysis. Borzello was raised in the Los Angeles suburb of Tarzana, an eighteen-mile jaunt on the 101 from Hollywood, and he told stories with a cinematic flair and an ear for dialogue. He spoke his mind. “Some guys think he’s abrasive,” former Cubs manager Dale Sveum said, “but he’s just brutally honest.” He made an ideal witness for the unveiling of Kershaw’s slider.

Borzello understood how a small change could transform a career. And if the pitch stank, Borzello wouldn’t be afraid to say so.

Borzello suggested Kershaw warm up with fastballs. Kershaw went through his motion. Up. Down. Break. The four-seamer displayed its usual life. Then Borzello called for a slider. Up. Down. Break. The pitch that emerged from Kershaw’s hand resembled a fastball until the moment before it arrived in Borzello’s glove. The average slider tended to make a diagonal dive, usually with more horizontal tilt than vertical descent. This ball was different. It plunged toward the earth like a split-fingered fastball, with little horizontal movement. “Like, it vanished,” Borzello recalled.

Kershaw made an inquisitive face, casting for approval. “Do that again,” Borzello said.

Up. Down. Break. The second slider charted the same course. Jesus, Borzello thought. Kershaw repeated his delivery and repeated the outcome. He felt the control he craved, the sensation that eluded him with his curveball. The ball went where he wanted it to go. “I could miss a little bit and still be close,” he recalled. After a few more, Kershaw asked Borzello for his input. “Are you kidding me?” Borzello said. “If you can do that off a mound, that’s game-ready.” Kershaw looked unsure. It was hard to fathom he had conjured a new third pitch so quickly. “We’ll see,” he said.

Borzello was not the only fortunate spectator that weekend at Wrigley. An injury created a temporary opening on the roster for A. J. Ellis. He had been toiling at triple-A Albuquerque, blocked in the majors by Russell Martin and the veteran backup Brad Ausmus. A day after Kershaw tested the slider, Borzello pulled Ellis aside. He needed Ellis to catch Kershaw’s bullpen session and analyze the new pitch. “Is he going to let me?” Ellis asked.

When Kershaw returned to the bullpen, Ellis crouched behind the plate. Honeycutt monitored Kershaw. Borzello stood next to Ellis. When the first slider arrived, Ellis looked up at Borzello, incredulous. “What’d I tell you?” Borzello said. The ball kept disappearing. From afar, the pitch did not look like much. Up close, it was a marvel. “It’s hard to explain unless you’ve caught,” Borzello recalled. “It’s hard because you don’t see spin.” The catcher and the instructor maintained the dialogue, wondering if they could believe their eyes. Even Honeycutt, a far more reserved observer, registered his approval. This might be the answer to Kershaw’s problem, the off-speed pitch he could land for a strike and throw when he trailed in the count. “It was supplying exactly what we were trying to do,” Honeycutt recalled.

The group gathered after Kershaw finished throwing. “What do you got on the slider?” Kershaw asked Ellis. “It’s game-ready,” he said.

That sent Borzello into a tizzy. “I told you!” he said. “I told you!”

“Relax,” Kershaw said. He had been down this road before. “I’m telling you,” Ellis said. “That is unbelievable.” Honeycutt was less effusive but still encouraged. He liked the shape of the pitch. He liked the depth. And he liked how different it looked.

Kershaw could already hide the ball using the delivery Skip Johnson taught him. The angle of his arm, combined with the grip Honeycutt showed him, created a weapon that few other pitchers could emulate. “I can’t emphasize enough how unique his slider is, compared to the rest of baseball,” Honeycutt recalled. The singularity of the offering opened another door for Kershaw. He had something no one else really had. Hitters relied on muscle memory. Their eyes recognized the incoming pitch and their body reacted. But what happened when they faced something they could not recognize?

Excerpted from THE LAST OF HIS KIND: Clayton Kershaw and the Burden of Greatness. Available on May 7. Copyright @2024 by Andy McCullough and reprinted with permission from Hachette Books/Hachette Book Group. All rights reserved.